For those who poured the concrete or set the rivets, building the three Cooper River bridges was a deadly job, claiming the lives of at least 19 workmen.

Falling may have been the biggest risk, but the single worst incident occurred deep below the surface on the river bottom.

"Caught like rats in a trap," declared a 1928 News and Courier article describing how seven black workmen were killed excavating one of the footings for the first span, the John P. Grace Memorial Bridge.

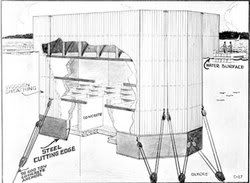

The men, known as "sandhogs," were in a supposedly water-tight caisson — a deeply sunk, cylindrical wooden box taller than three houses that dropped from the river's surface to its bottom. Once inside, the men could stay mostly dry as they undertook the well-paying but dirty job of removing tons of sand, mud and oyster shells.

Caisson

Disaster struck when the caisson at Grace's No. 10 footing abruptly shifted, opening a 29-degree crack between the caisson wall and the river, allowing mud and water to flood in on the men, covering them in a few seconds.

"It was as though a glass, inverted in a tub of water, had suddenly been tipped to allow a cushion of air to escape, and the water to take its place, filling the glass," the newspaper reported.

The deaths punctuated the ever-present risk of building the Grace Bridge, by far the more dangerous of the three spans that crossed the Cooper River between Charleston and Mount Pleasant during the 20th and 21st centuries.

Fourteen of the 19 worker deaths associated with all three bridges occurred on the Grace, while four died on the Silas Pearman Bridge in the 1960s. One worker died on the new Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge.

Other Grace victims include a worker who drowned after he was knocked off the bridge by a scaffolding beam; another who tried to save a friend from electrocution and himself received a fatal shock; and a worker whose head was split open by a piece of falling steel.

One man died in a crash when the tram he was driving ran out of control because the brakes failed. Another sandhog died from the bends, also known as "caisson disease," associated with working in heavy pressure below sea level. The others died in unspecified accidents.

Authors Jason Annan and Pamela Gabriel addressed the labor concerns of building the bridge in their 2002 book "The Great Cooper River Bridge."

"The project did employ basic safety procedures, though they pale in comparison to what is required today," the authors wrote.

"Photographs of the project indicate that bridge workers did not always wear hard hats and were not always using safety harnesses when working up on the 18-inch-wide steel beams of the trusses."

Safety regulations improved greatly by the time the Pearman Bridge was constructed in the 1960s, but reports indicate at least four workers died in falls.

The first victim was William Thompson, 34, of Shreveport, La. He was working 60 feet in the air when the pile-driving crane he was attached to by a safety belt toppled into the marsh, taking him down. The crane, weighing between 3,000 and 4,000 pounds, landed on him.

The Pearman's second victim was steelworker Sidney Wilson, 56, of Camp Hill, Pa., a foreman who lost his footing while climbing a ladder. He struck a wooden construction walkway as he tumbled 130 feet.

Eleven days later, carpenter Henry Padgett, 35, of Colleton County, fell. He may have been electrocuted when his steel measuring tape hit a live wire. The tape was found burned in two with about 23 feet of it extended from its reel. Strong winds may have blown the tape into a 46,000 volt power line that fed much of Mount Pleasant and the Charleston waterfront.

Pearman's last fatality was A.J. Hall, 27, of Cross, who plunged 150 feet when the three-wheeled power buggy he was driving went over the side. The vehicle was used to move lumber.

Hall's life vest ripped from his body when he hit the river.

The final construction death associated with spanning the Cooper River came in May 2004 on the Ravenel Bridge. Miguel Angel Rojas Lucas, 19, fell 75 feet into Town Creek. Investigators said Lucas was provided proper safety equipment at the time of his death but that he had unclipped his safety harness in preparation for his lunch break. His body was recovered three days later.